Edmund Burke Autograph Letter Signed on the French Translation of His Scathing 'Letter to a Noble Lord'

Two ways to bid:

- Leave a max absentee bid and the platform will bid on your behalf up to your maximum bid during the live auction.

- Bid live during the auction and your bids will be submitted real-time to the auctioneer.

Bid Increments

| Price | Bid Increment |

|---|---|

| $0 | $5 |

| $50 | $10 |

| $200 | $25 |

| $500 | $50 |

About Auction

Jan 10, 2024

RR Auction support@rrauction.com

- Lot Description

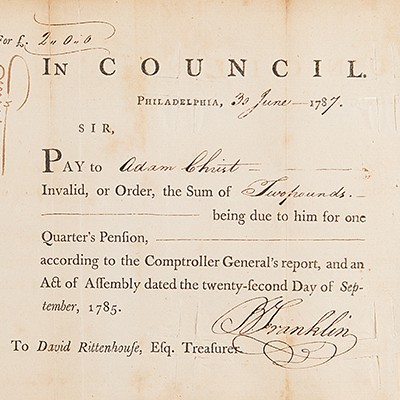

ALS signed “Edm. Burke,” three pages on two adjoining sheets, 7.5 x 9.5, March 17, 1796. Addressed from Beaconsfield, an interesting handwritten letter from Edmund Burke to Jean-Gabriel Peltier, the French translator of his famous work, ‘A Letter From the Right Honourable Edmund Burke to a Noble Lord: On the Attacks Made Upon Him and His Pension, in the House of Lords by the Duke of Bedford and the Earl of Lauderdale, Early in the Present Sessions of Parliament,’ one of his last significant works written in 1796, one year before his death. In this letter, Burke suggests some corrections and compares the possibilities of English vs French for expressing his ideas and style.

In part: “I have received your collection of interesting pieces with what is far more valuable, your own original judicious and entertaining remarks. Without them, many of the most important events in this wonderful course of Revolutions, which seems to form a system of this kind, could not be understood.

I am very sensible of the honour you have done me in amusing your leisure hours in a translation of any thing that comes from me. You seem to express the sentiments very perfectly, where there is no allusion or oblique sense. If there be any mistake, it is where there is some parody, some sarcasms or some matter of reference. I am very sensible of the difficulty of managing, in another language, sentences in which a variety of senses and matters are endeavoured to be combined and made to bear upon each other without a breach of unity and harmony. There are little equivoques, which if shown only in profile, are not starring with a broad face, produce a good effect. Here and there, in the keepsake they are lost as is p. 62. Bedford level cannot be applied to the county of Bedford, which is generally sandy, and barren. But to another Estate of...called Bedford Level. Nivelle Bedford. This allusion plays with the...Français. And the expression of low, flat and fat apply sarcastically, and in double sense. I have marked some other things for your own private satisfaction in the copy I send you. They can be of no use for correction. This translation, though excellent indeed, and beyond the merite of the piece, will hardly pass to a second impression as there are hardly a sufficient number of French readers in London to demand more than one; if so much as one, especially on a subject which so far it concerns me is personal, and of little importance to the publick.

As to what you say of the two languages, I believe you hardly do sufficient justice to your own, which as far as I am capable of judging, is equal to everything of which our language is susceptible. The difficulty of transposing into one language the spirit of another is a general difficulty. That part may be strong in one language which is weak in another, and this partial inequality is not sufficient to settle the balance in favour of any of them. Once more, Sir, permit me to thank you for the honour you have done me.”

Burke adds a postscript: “I believe I am in your debt for three years subscription, but I have been rendered inattentive by great affliction I shall write to a friend to discharge what I owe you with my best acknowledgments.” Peltier indeed published his translation of this book in London in 1797. In fine condition. An amusing and gracious letter from Burke to his translator, heaping praise on the latter’s adept balance of the English and French languages in regard to Burke’s noteworthy and often scathing reply to the Dukes of Bedford and Lauderdale, men who criticized Burke’s reception of a hefty pension, one awarded from the throne.

King George III, whose favour Burke had gained by his attitude on the French Revolution, wished to create him Earl of Beaconsfield. But the death of his son, Richard Burke, deprived him of the opportunity of such an honour, so the only award he would accept was a pension of £2,500. The reward was hastily attacked by the Duke of Bedford and the Earl of Lauderdale, to whom Burke replied, in the referenced ‘Letter to a Noble Lord,’ arguing that he was rewarded on merit, whereas the Duke of Bedford received his rewards from inheritance alone, his ancestor being the original pensioner: ‘Mine was from a mild and benevolent sovereign; his from Henry the Eighth.’ - Shipping Info

-

Bidder is liable for shipping and handling and providing accurate information as to shipping or delivery locations and arranging for such. RR Auction is unable to combine purchases from other auctions or affiliates into one package for shipping purposes. Lots won will be shipped in a commercially reasonable time after payment in good funds for the merchandise and the shipping fees are received or credit extended, except when third-party shipment occurs. Bidder agrees that service and handling charges related to shipping items which are not pre-paid may be charged to a credit card on file with RR Auction. Successful international Bidders shall provide written shipping instructions, including specified Customs declarations, to RR Auction for any lots to be delivered outside of the United States. NOTE: Declaration value shall be the item’(s) hammer price and RR Auction shall use the correct harmonized code for the lot. Domestic Bidders on lots designated for third-party shipment must designate the common carrier, accept risk of loss, and prepay shipping costs.

-

- Buyer's Premium

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB