Behind the Scenes at Auction: What Drives an Estimate

A few years ago, just before we were to sell a large collection of contemporary wall art (paintings, prints, etc.), a dealer from NYC confronted me in my auction hall and asked who exactly was responsible for the ultra-conservative estimates. When I told him I was he said, flatly, and not with a little attitude, “You are doing the artists and the art a great disservice.” What he really meant was that our low estimates, often no more than 20% of what galleries (like his) sold the work for a decade earlier, were undermining the prices he was asking for pieces by the same artists. My response was appropriately bland, “If the work is so cheap, you should bid on it.”

When you buy a work of art from a gallery (and sometimes from an auction), you should compare it to buying a new car you’ve just driven off the lot. You buy a car because you want it and will enjoy it, not because you’re investing in it. If you happen to purchase a car, or a painting, that goes up in value, that’s really grand. But, unless you hit the lottery or wait for a very long time, that’s not likely to happen.

I write this because, as an auction house specializing in modern fine and decorative art, we are often confronted with harsh economic realities of resale values. When Ms. Jones pays $30,000 for a “dinosaur” vase by Lino Tagliapietra, she’ll be lucky to get half of that out of the piece within a decade of her purchase. When Ms. Jones comes to us with her piece because she wants/needs to sell it, we find ourselves in the unenviable position of having to be the ones to tell her she’s probably going to lose money. That’s just the way it is for most contemporary art, at least for a while.

Collectors and galleries are often annoyed by our conservative approach to developing a secondary market for such work. By that, I mean the levels we believe are a true, barometer of what such things are worth once they are put on the block for the world to judge with their bidding paddles. Online Auctions are an immediate and transparent window into the psyches of collectors, dealers, and museums around the world, more than ever thanks to the Internet. We don’t necessarily construct that reality. We just create an open forum on which it plays out.

That said, we could influence the ultimate value of these objects. Obviously, if we choose to sell work by certain artists we must have faith in their validity. You’d be stunned to know what it costs an auction to put a piece up for sale and, if it doesn’t sell, we shoulder the loss. As such, our confidence level has to be fairly high, and we hedge our bets by estimating objects conservatively. Our reserves, or the minimum prices that must be met, are even lower. This is why so many of the artists, collectors, and galleries hold us in such disregard. Therein lies the silver lining.

About a decade ago we were lambasted by a very famous, contemporary designer because he thought we were killing his market with our low prices and not terribly higher results. We told him, “We understand your annoyance. But we are establishing your legacy. Low prices today establish a baseline that will influence future buyers. Give it some time.” We just sold several works by this very artist for well into six-figures, helping to burnish his already legendary status. He’s come to see auctions, ours and others, as part of an ongoing process that has increased the value and awareness of his work.

From here, the smart money focuses on objects by great living artists that are just finding their way to public auction. This is easy enough to determine because pricing databases will reveal with clarity how much of this work has actually sold at auction. If pieces by a glass artist such as William Morris sell new for $75,000, and you see a similar work at auction for $10 - $15,000, AND if you really like it and want to live with it, that might be the perfect time, the moment when the secondary market plays to your advantage. People are willing to put a lot of thought into buying stocks, but seem less inclined to do so when purchasing art. Buying art is supposed to be fun, after all. But those same clients, when expecting the kinds of returns and liquidity of art that a stock might bring, tend not to be as philosophical. Know what you’re buying and why you’re buying it. This won’t guarantee financial success, but it will certainly improve your odds.

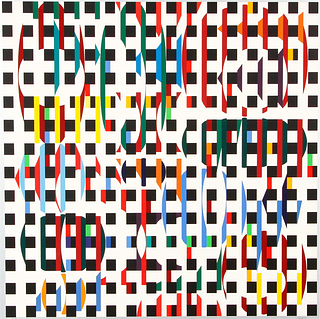

- Minimalism, Legacy, and the 90s Revival

- Island Light: Celebrating Nantucket Artists at Auction

- Gold, Silver & History: Five Standout Lots from Mebane’s U.S. Numismatic Auction

- A Brief History of Paper Dolls (and Why We Still Love Them)

- Artist Spotlight: Emile Pierre Branchard

- The Delphos Gown: Mariano Fortuny’s Timeless Revolution in Fashion

- Artist Spotlight: Charles Cary Rumsey, Artist & Athlete

- Reflections Through Time: A Brief History of Mirrors in the Home

- From the Gridiron to the Gallery: Super Bowl Inspired Finds on Bidsquare

- Miriam Haskell: The Legacy of an Iconic Costume Jewelry Designer

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB