Georgia O'Keeffe on the Ghost Ranch

A compact figure dressed in black, halved by a geometric sterling silver belt, crosses the desert with confident strides. Loose pieces of white hair, otherwise neatly gathered, wisp away from her sun wrinkled face. This bone gathering desert dweller isn’t just some nameless nomad, she is America's most cherished mother of modernist painting - Georgia O’Keeffe.

Georgia OKeeffe, From the Faraway, Nearby, Oil on Canvas, 1937, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

To mark the legendary artist's 128th birthday, Bidsquare took a brief look back at Georgia O’Keeffe’s ceremonious New Mexican home and studio on the famed Ghost Ranch. The prehistoric landscape of the eastern end of the Colorado Plateau, where the 21,000-acre ranch resides, inspired some of O’Keeffe’s most potent compositions. Expansive blue skies, erratic windstorms and carousels of light arrived everyday for O’Keeffe to absorb like a ritualistic time-lapse. The thin air, deep canyons and multicolored cliffs provided the artist with inexhaustible inspiration. One of her most beloved subjects, Cerro Pedernal, a narrow peak off of the Jemez Mountains, stood mightily in her front yard, easily seen through one of many panoramic windows in her home. She painted its rock face so many times, one could suggest she used it as a model posing as a subject. “ I thought someone could tell me how to paint a landscape, but I never found that person. I had to just settle down and try,” O’Keeffe admits, “ I thought someone could tell me how but I found nobody could. They could tell you how they painted their landscape but they couldn’t tell me to paint mine.”

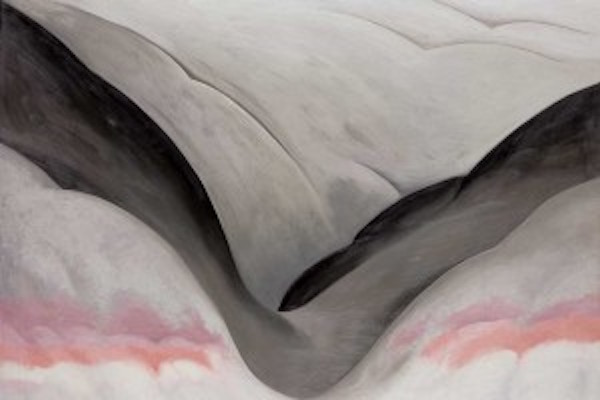

Georgia OKeeffe, Black Place, Grey and Pink," Oil on Canvas, 1949, Georgia OKeeffe Museum

The Ghost Ranch is also where O’Keeffe started picking animal bones instead of her internationally recognized flowers. The dramatic white deer antlers, cattle skulls and pelvic bones did not symbolize death to O’Keeffe, in the same way that she denied any correlation between her closely cropped flower paintings and the female anatomy. In her opinion, the bones were simply shapes she enjoyed, especially when held up like a view finder toward the elastic blue sky.

Georgia OKeeffe, Pedernal From the Ranch #1, Oil on Canvas, 1956, Minneapolis Institute of Art

Her adoration for the region was first felt during a summer visit to Taos, where upon spotting the Ghost Ranch from a faraway overlook, she proclaimed, “As soon as I saw it, I knew I must have it.” She was guided by a local man to the property in 1934, and although it wasn’t available to buy at the time, she stayed the night in a vacant room. She came to spend the entire summer (and every summer after that) at the Ghost Ranch until finally purchasing her own home just south of the Ghost Ranch in Abiquiu in 1945. Her spiritual ties to the sublime artist retreat reset her inner compass away from life in New York City and continued to draw her closer into the barren landscape of the American Southwest. It was rumored that the secluded plot of land she acquired, which only had one room at the time, hosted a ghost that deterred everyone from going there - except her. Unaffected and intrigued, O’Keeffe settled in, “…I took my pots and pans and moved them to Abiquiu. I knew that was now my home. Even though I continue to return to Ghost Ranch each summer to paint or whenever I can find an excuse to get there. When you start making a home, it is difficult to stop changing it, imagining it different. If I thought of building a house from scratch today, I would make it so simple that it would make most houses look like some kind of Chinese puzzle,” she said.

Top: Georgia OKeeffe and Her Houses, Ghost Ranch and Abiquiu; Left to Right: Skull and bones at Abiquiu, Architectural Digest; Interior at Abiquiu, Architectural Digest

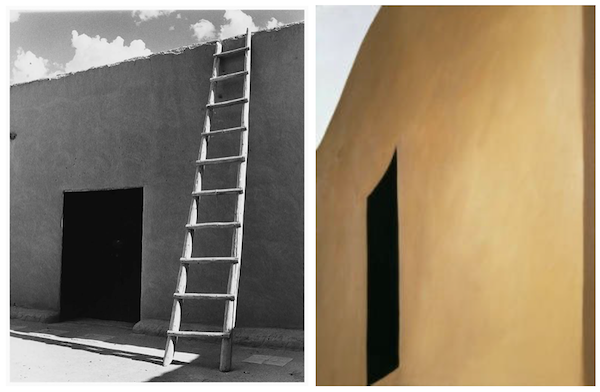

Abiquiu, just south of the Ghost Ranch, sits on a plateau at an elevation of 6,400 feet overlooking the Chama River Valley in Rio Arriba County, New Mexico. Her residence at Abiquiu became more permanent in 1946 after the death of her husband Alfred Stieglitz. The house, which was virtually uninhabitable when she bought it, grew as an extension of herself and remained simplistic in design as she used traditional Native American adobe techniques to rebuild it. Aside from her own artworks, the house follows no one aesthetic. Modern furniture, primal fireplaces and hanging animal skeletons set the mood within her rustic, wilderness retreat. Above all, the most important facet of the house is a simple, square black door; a shadowy opening which stands like an opened black eye. This small area of the house is the reason why O’Keeffe purchased the dilapidated structure in the first place. O’Keeffe obsessed over its enigmatic presence and repeatedly painted it across all seasons, times of day and angles.

Left to Right: Photograph of ladder in the patio at Abiquiu, At Home & Afield; Georgia OKeeffe, Black Patio Door, 1955, Oil on Canvas, Georgia OKeeffe Museum

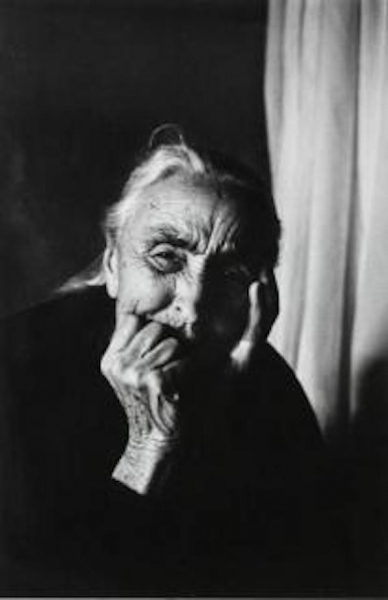

On November 11th, Leslie Hindman Auctioneers will feature an endearing, black and white portrait of O’Keeffe pictured in her Abiquiu home. The image, taken by famed American Civil Rights photographer, Dan Budnick is a rare image of the reclusive artist who barely invited media to her cherished hideaway. The photograph, Georgia OKeeffe After Supper, Ghost Ranch, New Mexico, March 1975 is especially personal as she was known for her schedule of hour long walks in the morning, afternoon and evening divided by humble meals and studio sessions. Her soft smile and kind eyes are framed by the strong, humble hands that bravely pioneered American Modernist painting for both male and female artists alike.

Dan Budnik, Georgia OKeeffe After Supper, Ghost Ranch, New Mexico, March 1975, Lot 164 in Leslie Hindman Auctioneers November 10 Auction

Georgia O’Keeffe wasn’t just an authentic female artist. She carried herself as a genderless force of nature who constantly challenged the human experience and the critical interpretation of her work. Even at the ripe age of 86, she enjoyed climbing up the ladder, which rested on the side of her U-shaped adobe home, to gaze out over the roof with a sense of wonderment - looking beyond the slopes of the Chama River Valley, as if discovering it for the very first time.

- Preview the December Doyle+Design Auction: A Celebration of Modern & Contemporary Mastery

- Billings Winter Design 2025: A Celebration of Modern Mastery Across Eras

- The Ultimate Holiday Gift Guide: Luxe Finds From Bidsquare’s Finest Auctions

- Fine & Antique Jewelry Sale: A Curated Journey Through Craftsmanship & Design

- Upcoming Auction Spotlight: Doyle’s Fine Art: 19th Century & Early Modernism

- Entertain with Style This Holiday Season: Highlights from Doyle’s December 8 Auction

- Six Standout Lots from Newel’s Fine Jewelry, Timepieces & Luxury Handbags Sale

- Artist Spotlight: Roy Lichtenstein, Pop Art’s Master of Bold Lines & Bigger Ideas

- Discover the Warmth of Pennsylvania Impressionism: Nye & Co.’s Dec. 3 Auction Features the Collection of Nancy & Robert Stein

- Inspired by Cape Cod: The Artists Who Paint Its Light, History, and Character

EUR

EUR CAD

CAD AUD

AUD GBP

GBP MXN

MXN HKD

HKD CNY

CNY MYR

MYR SEK

SEK SGD

SGD CHF

CHF THB

THB